Jump to page sections

- The foreach Keyword

- The foreach Loop's Syntax

- Some foreach Loop Examples

- A Basic foreach Loop Example

- Another foreach Loop Example

- Example With A Pipeline

- LINQ foreach

- Iterating A Variable

- The continue And break Keywords

- The Special $foreach Variable

- Labelled foreach Loops

- The ForEach-Object cmdlet

- The ForEach-Object cmdlet's Syntax

- Pipeline Objects Are Generated And Processed One At A Time

- Spanning Multiple Lines

- Multiple Script Blocks

- Flattening Of Arrays

- Some ForEach-Object Examples

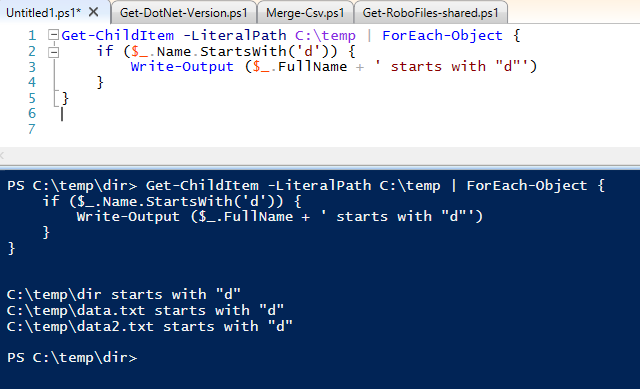

- A Basic ForEach-Object Example

- Random Example

- Multiple Script Blocks Passed To ForEach-Object

- With An End Block As Well

- Using Explicit Parameter Names For The Script Blocks

- Hacking The continue Keyword In A ForEach-Object

A bit confusingly (but conveniently), you can use both the shorthand (aliases) "%" and "foreach" instead of ForEach-Object in a pipeline. The logic behind that is as follows: If the word foreach is used at the beginning of a statement (or after a label), it's considered the foreach loop keyword, while if it's anywhere else, it'll be recognized as the ForEach-Object cmdlet/command. A cmdlet is a type of command.

As for the alias "%", this also doubles as the modulus operator, if used as a binary operator - one that takes an argument on both sides. Such as "10 % 1". I talk more extensively about this below.For an article about the "regular" PowerShell for loop, click here.

This article was written about PowerShell version 2, which is the default in Windows 2008 R2 and Windows 7.On 2021-12-10, I added some notes about LINQ foreach.

The foreach Keyword

The foreach loop enumerates/processes the entire collection/pipeline before starting to process the block (statement list / code), unlike the pipeline-optimized Foreach-Object cmdlet which processes one object at a time.

You can not specify a type for the variable in a foreach loop. The error you will get if you try is:

PS E:\temp> foreach ([int]$var in 1..3) { $var }

Missing variable name after foreach.

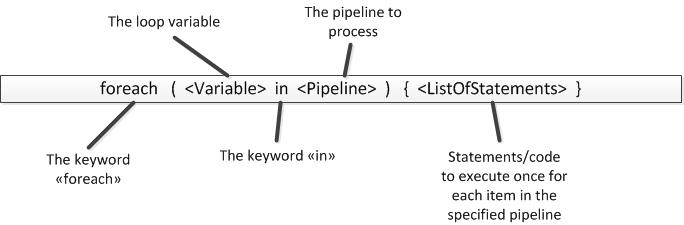

The foreach Loop's Syntax

Some foreach Loop Examples

A Basic foreach Loop Example

PS C:\> foreach ($Num in 1, 2, 3) { $Num }

1

2

3

PS C:\> $Num

3

You can also assign the results to an array, like this:

PS C:\> $Array = foreach ($i in 1..3) { $i }

PS C:\> $Array

1

2

3

PS C:\>

Another foreach Loop Example

The loop below gets all numbers between 1 and 50 that are evenly divisible by 10, using the modulus operator. The modulus operator (%) returns zero when there is no remainder and the number is evenly divisible. Zero is considered false - unless it's a string ("0" or '0' or any other crazy unicode quote character - wow, terrible decision...).

I should mention that if PowerShell sees a "%" in the middle of a pipeline, it will interpret it as the ForEach-Object cmdlet. "%" is only the modulus operator when it's used as a binary operator. A binary operator means it has an argument on both its left and right side, while a unary operator usually only has something on its right-hand side, and always only one argument in that latter unary case.

The range operator ".." (two periods) enumerates ranges of integers between the start and end integer specified. If you specify a decimal number, it will be cast to the [int] type. PowerShell uses what is called "banker's rounding" and rounds N.5 numbers to the closest even integer, so 1.5 is rounded to 2 and 2.5 is also rounded to 2.

PS C:\> foreach ($Integer in 1..50) { if ( -not ($Integer % 10) ) { "$Integer is like totally divisible by ten" } }

10 is like totally divisible by ten

20 is like totally divisible by ten

30 is like totally divisible by ten

40 is like totally divisible by ten

50 is like totally divisible by ten

PS C:\>

A way that I personally find a bit easier to understand for this specific case, is using "-eq 0":

PS C:\> foreach ($Integer in 1..10) { if ($Integer % 10 -eq 0) { "$Integer is like totally divisible by ten" } }

10 is like totally divisible by ten

Example With A Pipeline

PS C:\> $Sum = 0

PS C:\> foreach ($File in dir -Path e:\temp | Where { -not $_.PSIsContainer }) { $Sum += $File.Length }

Let's look at the sum.

PS C:\> $Sum 362702012

There's a built-in constant for "MB" which allows you to do this to easily determine the size is about 346 MB:

PS C:\> $Sum/1MB 345.899593353271

LINQ foreach

With PowerShell version 4 came "LINQ" support. My knowledge about this is superficial. I will demonstrate ".where()" and ".foreach()" on arrays.

Let's dive right in with some examples.

PS /home/joakim/Documents> @(0, 1, 2, 3).foreach({$_ * 2})

0

2

4

6

PS /home/joakim/Documents> @(0, 1, 2, 3).where({

$_ % 2 -eq 0}).foreach({$_ * 2})

0

4

I will also show that it works without the parentheses, a not-very-known fact.

PS /home/joakim/Documents> @(0, 1, 2, 3).foreach{$_ * 2}

0

2

4

6

This is quirky and definitely not best practices. If you add a space, like you can with ForEach-Object, it will produce a syntax error.

PS /home/joakim/Documents> @(0, 1, 2, 3).foreach {$_ * 2}

ParserError:

Line |

1 | @(0, 1, 2, 3).foreach {$_ * 2}

| ~

| Unexpected token '{' in expression or statement.

Iterating A Variable

PS C:\> $NegativeNumbers = -3..-1

PS C:\> foreach ($NegNum in $NegativeNumbers) {$NegNum * 2}

-6

-4

-2

The continue And break Keywords

Here's a quick demonstration:

PS C:\> $Numbers = 4..7

PS C:\> foreach ($Num in 1..10) {

if ($Numbers -Contains $Num) {

continue

}

$Num

}

1

2

3

8

9

10

And here's an example of break:

PS C:\> foreach ($Num in 1..10) {

if ($Numbers -Contains $Num) {

break

}

$Num

}

1

2

3

PS C:\>

If you have nested loops that aren't labelled, continue and break will act on the innermost block. As demonstrated here:

PS C:\> foreach ($Num in 1..3) {

foreach ($Char in 'a','b','c') {

if ($Num -eq 2) { continue }

$Char * $Num # send this to the pipeline

}

}

a

b

c

aaa

bbb

ccc

PS C:\>

The Special $foreach Variable

This will give you odd numbers between 1 and 10:

PS C:\> foreach ($Int in 1..10) {

$Int; $foreach.MoveNext() | Out-Null }

1

3

5

7

9

PS C:\>

Another use you might have for it, is if you have an array, and need to get the next item after some condition is met. It can save you from setting flags, although it's about as clunky. Here's an example where I want the first letter after I've matched "c" (so I get "d").

PS C:\> "$Array"

a b c d e f g

PS C:\> foreach ($Letter in $Array) { if ($Letter -ieq 'c') {

>> $null = $foreach.MoveNext(); $foreach.Current; break } }

>>

d

PS C:\>

To suppress the unwanted boolean output from $foreach.MoveNext(), you can also cast the results to the void type accelerator:

[void] $foreach.MoveNext()

I'll toss in a real-world example where you have an array of values where every other element can be used as a key and a value in a hashtable:

PS C:\> "$Array" Name John Surname Smith Occupation Homeless

To add this to a hash, you can use something like this:

PS C:\> $Hash = @{}

PS C:\> foreach ($Temp in $Array) {

>> $Key = $Temp; [void] $foreach.MoveNext();

>> $Value = $foreach.Current; $Hash.Add($Key, $Value) }

>>

PS C:\> $Hash.GetEnumerator()

Name Value

---- -----

Name John

Surname Smith

Occupation Homeless

PS C:\>

That was meant to be explicit. In the real world you would probably rather write something like this:

PS C:\> $Hash = @{}

PS C:\> foreach ($t in $Array) { [void] $foreach.MoveNext(); $Hash.$t = $foreach.Current }

PS C:\> $Hash

Name Value

---- -----

Name John

Surname Smith

Occupation Homeless

Side note: In Perl you can simply assign an array or list to a hash and this is done automatically - with a warning if there's an odd number of elements in the list/array. The Perl code would simply be: my %hash = @array;

Labelled foreach Loops

Here's an example of some code where the outermost loop is labelled with the ":OUTER " part before the foreach keyword, indicating the name of the label (OUTER). When you use the continue or break keywords, you pass this label name as the first argument, to indicate the block to break out of (if no argument is passed, the innermost block is targeted).

:OUTER foreach ($Number in 1..15 |

Where { $_ % 2 }) {

"Outer: $Number"

foreach ($x in 'a', 'b', 'c') {

if ($Number -gt 5) {

continue OUTER

}

$x * $Number

}

}

This will produce output like this:

PS D:\temp> .\labeled-loop.ps1 Outer: 1 a b c Outer: 3 aaa bbb ccc Outer: 5 aaaaa bbbbb ccccc Outer: 7 Outer: 9 Outer: 11 Outer: 13 Outer: 15

The ForEach-Object cmdlet

Inside the block with the code/statements, the current object in the pipeline is accessible in a so-called automatic variable called "$_". So, to access the "Name" property of an object inside the ForEach-Object script block, you would use "$_.Name" (or "$_ | Select -ExpandProperty Name").

The ForEach-Object cmdlet's Syntax

The syntax is as follows:

| ForEach-Object { } [| ]

It can also take a begin and end block:

| ForEach-Object -Begin { } -Process { } -End { } [| ]

Pipeline Objects Are Generated And Processed One At A Time

Spanning Multiple Lines

It can look like the following:

Multiple Script Blocks

The begin block is executed before pipeline object processing begins, then the objects from the pipeline are processed one at a time in the process block, and finally the end block is run after all objects have been processed.

If you specify a ForEach-Object -Begin { } -End { } and then add more script blocks, they will be treated as multiple process blocks.Flattening Of Arrays

$NestedArray2 = $NestedArray1 | %{ , $_ }

That would preserve the nesting. The process of flattening the array is referred to as "unraveling" and that it does this was a design choice by the PowerShell development team. Most of the time it's what you want when working at the command line.

Examples of how this preserves nesting:

PS D:\temp> ( @(1,2,3), @(4,5,6) | %{ , $_ } ).Count

2

And with unraveling:

PS D:\temp> ( @(1,2,3), @(4,5,6) | %{ $_ } ).Count

6

Some ForEach-Object Examples

A Basic ForEach-Object Example

PS C:\> 2..4 | ForEach-Object { $_ }

2

3

4

PS C:\>

To store them in a variable for later use after the processing, just assign to a variable at the start of the line, like this:

PS C:\> $MyVariable = 0..3 | foreach { $_ * 2 }

PS C:\> $MyVariable

0

2

4

6

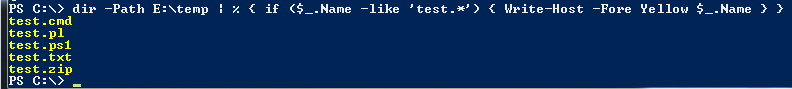

Random Example

PS C:\> dir -Path E:\temp | % { if ($_.Name -like 'test.*') {

Write-Host -Fore Yellow $_.Name} }

test.cmd

test.pl

test.ps1

test.txt

test.zip

PS C:\>

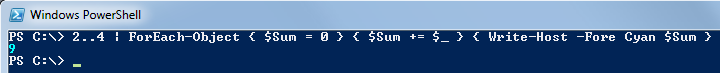

Multiple Script Blocks Passed To ForEach-Object

I mentioned in the introductory text that ForEach-Object can take multiple script blocks. Here's an example that demonstrates the begin block, with two script blocks specified for ForEach-Object.

PS C:\> $Sum = 10

PS C:\> 2..4 | ForEach-Object { $Sum += $_ }

PS C:\> $Sum

19

PS C:\> # omg, wrong

PS C:\> 2..4 | ForEach-Object { $Sum = 0 } { $Sum += $_ }

PS C:\> $Sum

9

PS C:\> # that's more like it

There you can see that I initialize $Sum to 0 in the begin block in the second ForEach-Object example.

With An End Block As Well

Now, if you want to do something after all the objects in the pipeline have been processed, you can put it in the end block. Here's the same example as above including an end block.

PS C:\> 2..4 | ForEach-Object { $Sum = 0 } { $Sum += $_ } { $Sum }

9

Using Explicit Parameter Names For The Script Blocks

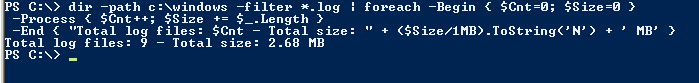

PS C:\> dir -path c:\windows -filter *.log | foreach -Begin { $Cnt=0; $Size=0 }

-Process { $Cnt++; $Size += $_.Length }

-End { "Total log files: $Cnt - Total size: " + ($Size/1MB).ToString('N') + ' MB' }

Total log files: 9 - Total size: 2.68 MB

PS C:\>

Hacking The continue Keyword In A ForEach-Object

Since ForEach-Object uses a script block, you can't break out of it with the continue keyword that's used for foreach and for loops. You can use the return statement instead to achieve a similar result. If you do use the continue keyword, it will act like the break keyword in a foreach, while or for loop. If you do use break in a ForEach-Object, it will act the same as continue. Note that the end block will also be skipped this way, if present.

PS C:\> $Numbers = 4..7

PS C:\> 1..10 |

%{ if ($Numbers -contains $_) {

return

}; $_ }

1

2

3

8

9

10

And with continue we see that it stops processing the remainder of the pipeline:

PS C:\> $Numbers = 4..7

PS C:\> 1..10 |

%{ if ($Numbers -contains $_) { continue }; $_ }

1

2

3

PS C:\>

Powershell

Windows

Blog articles in alphabetical order

A

- A Look at the KLP AksjeNorden Index Mutual Fund

- A primitive hex version of the seq gnu utility, written in perl

- Accessing the Bing Search API v5 using PowerShell

- Accessing the Google Custom Search API using PowerShell

- Active directory password expiration notification

- Aksje-, fonds- og ETF-utbytterapportgenerator for Nordnet-transaksjonslogg

- Ascii art characters powershell script

- Automatically delete old IIS logs with PowerShell

C

- Calculate and enumerate subnets with PSipcalc

- Calculate the trend for financial products based on close rates

- Check for open TCP ports using PowerShell

- Check if an AD user exists with Get-ADUser

- Check when servers were last patched with Windows Update via COM or WSUS

- Compiling or packaging an executable from perl code on windows

- Convert between Windows and Unix epoch with Python and Perl

- Convert file encoding using linux and iconv

- Convert from most encodings to utf8 with powershell

- ConvertTo-Json for PowerShell version 2

- Create cryptographically secure and pseudorandom data with PowerShell

- Crypto is here - and it is not going away

- Crypto logo analysis ftw

D

G

- Get rid of Psychology in the Stock Markets

- Get Folder Size with PowerShell, Blazingly Fast

- Get Linux disk space report in PowerShell

- Get-Weather cmdlet for PowerShell, using the OpenWeatherMap API

- Get-wmiobject wrapper

- Getting computer information using powershell

- Getting computer models in a domain using Powershell

- Getting computer names from AD using Powershell

- Getting usernames from active directory with powershell

- Gnu seq on steroids with hex support and descending ranges

- Gullpriser hos Gullbanken mot spotprisen til gull

H

- Have PowerShell trigger an action when CPU or memory usage reaches certain values

- Historical view of the SnP 500 Index since 1927, when corona is rampant in mid-March 2020

- How Many Bitcoins (BTC) Are Lost

- How many people own 1 full BTC

- How to check perl module version

- How to list all AD computer object properties

- Hva det innebærer at særkravet for lån til sekundærbolig bortfaller

I

L

M

P

- Parse openssl certificate date output into .NET DateTime objects

- Parse PsLoggedOn.exe Output with PowerShell

- Parse schtasks.exe Output with PowerShell

- Perl on windows

- Port scan subnets with PSnmap for PowerShell

- PowerShell Relative Strength Index (RSI) Calculator

- PowerShell .NET regex to validate IPv6 address (RFC-compliant)

- PowerShell benchmarking module built around Measure-Command

- Powershell change the wmi timeout value

- PowerShell check if file exists

- Powershell check if folder exists

- PowerShell Cmdlet for Splitting an Array

- PowerShell Executables File System Locations

- PowerShell foreach loops and ForEach-Object

- PowerShell Get-MountPointData Cmdlet

- PowerShell Java Auto-Update Script

- Powershell multi-line comments

- Powershell prompt for password convert securestring to plain text

- Powershell psexec wrapper

- PowerShell regex to accurately match IPv4 address (0-255 only)

- Powershell regular expressions

- Powershell split operator

- Powershell vs perl at text processing

- PS2CMD - embed PowerShell code in a batch file

R

- Recursively Remove Empty Folders, using PowerShell

- Remote control mom via PowerShell and TeamViewer

- Remove empty elements from an array in PowerShell

- Remove first or last n characters from a string in PowerShell

- Rename unix utility - windows port

- Renaming files using PowerShell

- Running perl one-liners and scripts from powershell

S

- Sammenlign gullpriser og sølvpriser hos norske forhandlere av edelmetall

- Self-contained batch file with perl code

- Silver - The Underrated Investment

- Simple Morningstar Fund Report Script

- Sølv - den undervurderte investeringen

- Sort a list of computers by domain first and then name, using PowerShell

- Sort strings with numbers more humanely in PowerShell

- Sorting in ascending and descending order simultaneously in PowerShell

- Spar en slant med en optimalisert kredittkortportefølje

- Spre finansiell risiko på en skattesmart måte med flere Aksjesparekontoer

- SSH from PowerShell using the SSH.NET library

- SSH-Sessions Add-on with SCP SFTP Support

- Static Mutual Fund Portfolio the Last 2 Years Up 43 Percent

- STOXR - Currency Conversion Software - Open Exchange Rates API